The Space Ambitions of China, Russia and USA

When Apollo 14 astronaut Edgar Mitchell returned to Earth in 1974, the United States and the Soviet Union were in the thick of the Cold War that had threatened the planet’s survival. But to Mitchell, being in space provided a different perspective.

“From out there on the moon,” he told People magazine, “international politics look so petty.”

As Mitchell was splashing down in the Pacific Ocean, the two countries were already laying the foundation for cooperation in space policy.

A year later, the superpowers would launch the joint Apollo-Soyuz Test Project signaling the countries’ intent to work together in space in the decades to come. The two countries would remain unrivaled until the rise of the Chinese space program in the 1990s.

Today, the U.S. and Russian space agencies have been more collaborative than the governments that fund them.

“Space cooperation has been a hallmark of U.S.-Russia relations, including during the height of the Cold War,” said NASA spokesman Dan Huot. That cooperation is also the foundation for what Huot calls “the largest and most complex spacecraft ever flown”: the International Space Station.

A Look at the Station

Space agencies from 15 countries have been involved with the space station since its launch in 1998. An army of construction, processing, mission operations support, research and communications facilities spanning the globe are required to keep the station and its international rotation of astronauts flying. Even the station itself is a hodgepodge of modules and parts from around the world, built in phases over two decades.

“Elements launched from different countries and continents are not mated together until they reach orbit, and some elements that have been launched later in the assembly sequence were not yet built when the first elements were placed in orbit,” Huot said.

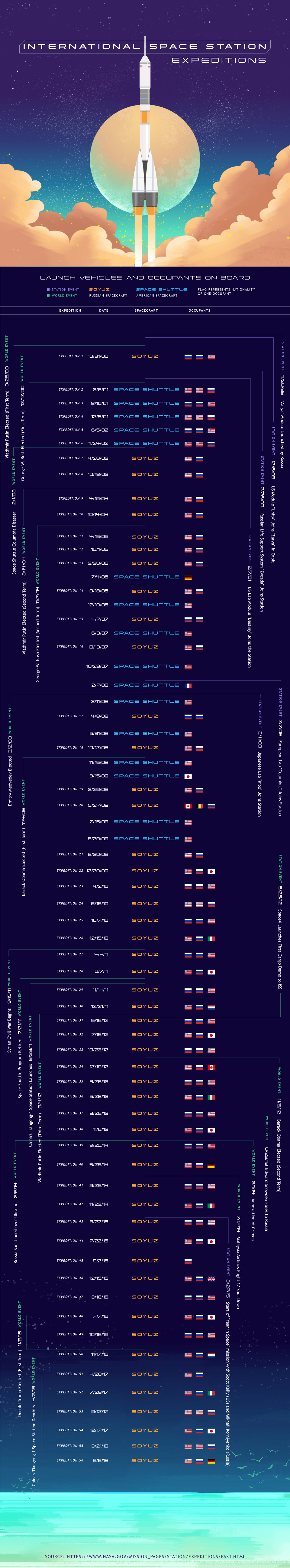

Of all the contributing nations, the U.S. and Russia supply the most in terms of personnel and operations. Until NASA’s final space shuttle mission in 2011, expeditions to the station were launched on either American shuttles or Russian Soyuz rockets. Of the 162 astronauts that spent time on the station, 140 were American astronauts or Russian cosmonauts. NASA continues to buy seats on Soyuz rockets at $81 million each. In 2016 Charles Bolden, NASA administrator, said he expected the U.S. would not have “an all-American vehicle or an all-Russian vehicle ever again.”

There have been 56 ISS expeditions, involving more and more countries over time. Expedition 20 stands out to Huot — it expanded the ISS crew from three to six, and included crewmembers from the U.S., Russia, Japan, Belgium and Canada.

The Rise of the Chinese National Space Agency

The U.S. and Russia were the first nations to have the resources to act on their space ambitions. For most of the space race, they were the only countries with such capabilities. China’s emergence as a global superpower came later, but now their space agency has the funding and experience to start challenging the longstanding duopoly. Since its latest inception in 1993, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) has managed to put a man in space, launch and briefly dock with its own space station and put a lander on the moon. It has ambitions to collaborate with other nations on manned landings to the moon and Mars.

The U.S. is not one of those nations, at least for the time being. Because of a clause inserted into the 2011 federal budget that effectively banned NASA from any cooperation with China, the nation has been excluded from ISS projects.

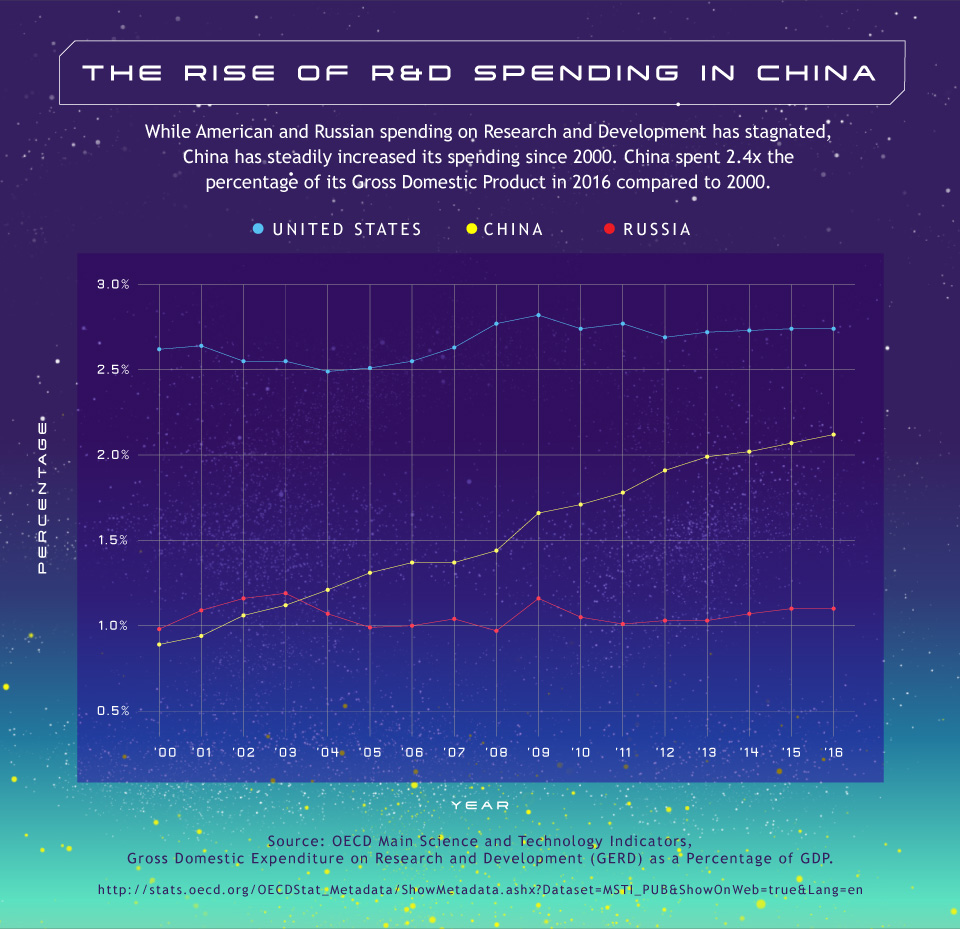

That hasn’t hampered China’s progress. The country now spends over 2 percent of its annual gross domestic product on science, eclipsing the percentage spent by the Russians in 2004 and approaching the 2.74 percent the U.S. spends on science each year.

View the text-only version of this graphic.

Divergent Agencies and Approaches

The ISS is one example of international cooperation in space, but the American, Russian and Chinese space agencies have begun adopting alternate structures and priorities.

Russia and China have moved forward with state-run approaches. Russia’s space agency, formerly known as Roscosmos, merged with the state-run United Rocket and Space Corporation in 2015 to focus on heavy-lift rockets.

China’s program has always been a product of the state. Consequently, it’s difficult to track the CNSA’s scope and funding, and there are echoes of the 1960s space race in its military ties. The agency has also been focused on extending its collaborative efforts with other space agencies.

During Barack Obama’s administration, NASA explored greater collaboration with private companies like SpaceX and Orbital ATK for launch vehicles and resupply missions. In 2010, Obama canceled NASA’s plans to return to the moon, and the U.S. has been without human spaceflight capabilities for nearly a decade.

View the text-only version of this graphic.

Citation for this content: American University’s International Relations Online Degree