A Beginner’s Guide to Environmental Agreements

Think of them as signature-filled superheroes with an ambitious, crucial mission: They are the thousands of treaties—crafted by diplomatic staffers, agreed to by governments, and enforced by law—out there trying to save the world. Some have more powers than others. Just a few have name recognition. Many are misunderstood.

International environmental agreements are a category of treaties with political and economic ramifications beyond their environmental impact, yet many people are unfamiliar with their specifics. The search term “What is the Paris Agreement?” reached peak popularity the day after the United States announced intent to withdraw from the treaty.

Despite confusion, people care about the ramifications of environmental agreements. A 2017 Gallup survey found Americans’ concern regarding global warming is at a three-decade high.

So, what do we need to know about environmental treaties, and how can we better understand why they matter?

What is an international environmental agreement?

International environmental agreements (IEAs) are signed treaties that regulate or manage human impact on the environment in an effort to protect it.

International

To qualify as international, the treaty must be intergovernmental; bilateral agreements are between two governments, and multilateral agreements are between more than two.

Environmental

The term environmental is broad. Some agreements encompass a range of environmental protections, while others are extremely specific. The International Environmental Agreements Database Project separates agreements into the following environmental categories:

- Nature: conservation and protection of resources and systems

- Species: interaction with mammals, agriculture, and marine life

- Pollution and climate: pollution of the air, land, oceans, and freshwater systems

- Habitat and oceans: maintaining ecosystems

- Freshwater resources: regulation of lakes and rivers

- Energy, nuclear issues, and conflict: energy production, nuclear-weapon-free zones, and environmental weapons (bacteriological, chemical, toxin)

Agreement

The names of IEAs can be confusing—why are some protocols and others are conventions?

A convention can refer to an actual meeting or conference between parties where they reach an agreement on the final terms of a treaty. However, it is also broadly used to describe wide-scale agreements between governments.

A protocol is usually supplemental: It further amends an existing convention and creates additional restrictions or standards. Original signatories of a convention are not automatically bound to protocols without a separate ratification.

Who participates in international environmental agreements?

Representatives from countries can accept and sign the terms of an international agreement on behalf of their government, making their country a signatory. The European Union (EU) also has the authority to sign treaties under international law and is often party to environmental agreements, in addition to the countries within it.

Signature vs. Ratification

A signature is not the last step. Ratification by the state’s governing body is required before countries are full participants in international agreements. While a signature is interpreted as a commitment to moving forward with full ratification, that’s not always the case.

For example, the United States is a signatory of the Basel Convention, a transboundary regulation on the movement and disposal of hazardous waste and materials. The United States signed the Basel Convention in 1990, one year after its adoption, but has yet to implement legislation to ratify it.

This means that although the state advised to participate initially, it is not technically a party in the convention.

The graphic below compares the Group of Seven (G7) and BRICS countries across measures such as GDP, participation in environmental agreements, CO2 emissions, and use of renewables.

The G7 is an informal group of seven industrialized democracies representing more than half the world’s wealth. Members include Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

BRICS countries are major developing nations with emerging economies. Members include Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.

Adopting renewable energy sources and reducing CO2 emissions are common goals of environmental agreements. They can also be indicators of a country’s larger environmental shifts. The United States, for example, increased contribution of renewables to energy production by 27 percent between 1990 and 2015 and reduced CO2 emissions per capita by 21 percent.

Countries like the United Kingdom, Germany and South Africa are seeing even more positive shifts in their use of renewables, with increases ranging from 530 to 773 percent. Some emerging nations like Brazil and India exhibit negative trends — increasing CO2 emissions by 54 and 156 percent, respectively. Also, their use of renewables as a proportion of total energy production is decreasing.

When do governments sign international environmental agreements?

Adoption vs. Entry Into Force

Adoption is the establishment of the treaty or agreement, and the first point at which governments can begin to sign. After adoption, parties can sign at will. This can happen immediately or years later.

For example, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES) was first ratified by the United States in 1974. However, additional members have joined as recently as 2016.

Entry into force is the date when a treaty goes into effect for members. The agreement determines when entry into force occurs, usually after a predetermined amount of time and when countries have ratified.

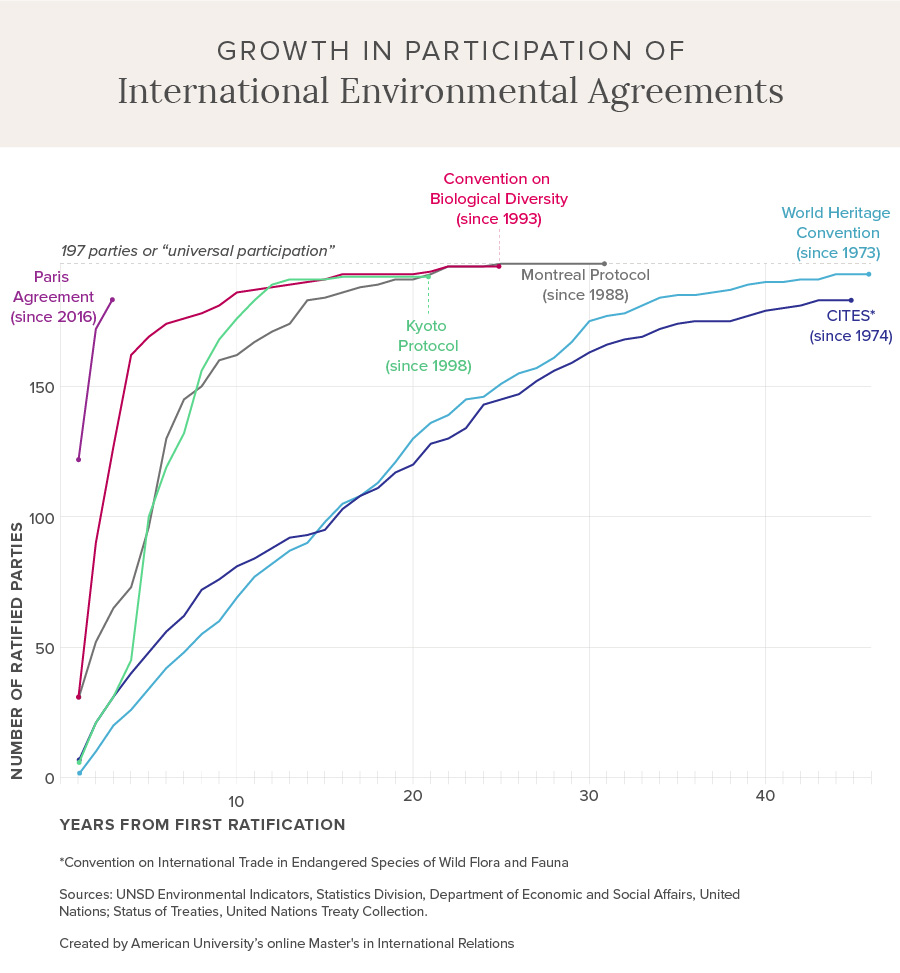

The graphic below shows how some of the largest IEAs grew over time.

The adoption of international environmental agreements by country has gotten faster over time.

It took the World Heritage Convention and CITIES agreements, first ratified in the 1970s, 16 years to be ratified by over 100 countries. The Kyoto Protocol however, was first ratified in 1998 and only took five years to reach the same point and the Paris Agreement (2016) received 121 ratifications in its first year.

How do international environmental agreements work?

Binding vs. Nonbinding Measures

As treaties, IEAs are governed by international law and binding once entered into force. However, that does not always translate to compliance. Domestic legislation is usually required to meet the standards of an environmental agreement.

The IEA itself can include mechanisms for treaty compliance (PDF, 981KB): consequences for failure to meet the agreed-upon standards or incentives to do the opposite. Some examples include performance reviews, financial assistance, and stricter requirements.

Action plans, directives, and commissions are examples of nonbinding environmental measures. Signatories are not legally obligated to fulfill the requirements or terms, so nonbinding measures can serve as political indicators of government intent.

What are some examples of international environmental agreements?

Below are six examples of IEAs with some of the highest rates of participation across the world.

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES)

Parties: 183 members

Adopted: March 3, 1973

Entered into force: July 1, 1975

Type: Species

G7 and BRICS membership:

The goal of CITES is to regulate the international trade of selected endangered plants and animals. There are almost 36,000 plants and animals protected by CITES, and species are grouped into three levels of protection depending on the degree of regulation required.

Learn more about the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna.

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

Parties: 196 members

Adopted: June 5, 1992

Entered into force: December 29, 1993

Type: Species

G7 and BRICS membership:

The goal of the CBD is to promote the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, with a focus on a shared system of costs and benefits among countries. It covers all ecosystems and species. This convention includes the Cartagena and Nagoya Protocols (PDF, 188KB), entered into force in 2003 and 2014, respectively.

Learn more about the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Kyoto Protocol

Parties: 192 members

Adopted: December 11, 1997

Entered into force: February 16, 2005

Type: Pollution and climate

G7 and BRICS membership:

The Kyoto Protocol supplements the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change to limit greenhouse gas emissions. The protocol gives countries specific targets to reduce emissions of six greenhouse gases. Thirty-seven countries and the EU participated in the first commitment period until 2012. The Doha Amendment is the second period and ends in 2020.

Learn more about the Kyoto Protocol.

The Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer

Parties: 197 members

Adopted: September 16, 1987

Entered into force: January 1, 1989

Type: Pollution and climate

G7 and BRICS membership:

The Montreal Protocol, of the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer, phases out production and use of ozone-depleting chemicals to help prevent health threats like skin cancer. The first treaty to achieve universal participation, the Montreal Protocol is largely considered a success. It has helped prevent an additional 280 million cases of skin cancer, according to an EPA report on ozone calculations.

Learn more about the Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer.

Paris Agreement

Parties: 184 members

Adopted: April 22, 2016

Entered into force: November 4, 2016

Type: Pollution and climate

G7 and BRICS membership:

The United States of America announced intent to withdraw

Part of the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Paris Agreement’s goal is to keep this century’s global temperature rise below 2 degrees Celsius. Measures to achieve success include mandatory emissions reporting, a new technology framework, and global stocktaking every five years.

Learn more about the Paris Agreement.

World Heritage Convention

Parties: 193 members

Adopted: November 23, 1972

Entered into force: December 17, 1975

Type: Nature

G7 and BRICS membership:

The goal of the World Heritage Convention is to identify and preserve potential sites important to cultural and natural heritage. Places selected as World Heritage Sites are protected under international law and can be eligible for international financial assistance. Sites in the United States include Yellowstone National Park, Independence Hall, and the Statue of Liberty.

Learn more about the World Heritage Convention.

The following section includes tabular data from the data visualizations in this post.

Environmental Agreements, CO2 Emissions, and Renewable Energy by Country↑

| Country | Population (millions) | GDP (trillions) (USD 2016) | Number of Ratifications | CO2 per capita – percent change since 1990 | Contribution of Renewables – percent change (1990 to 2015) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

France | 67.1 | 2.58 | 270 | -23 | 13 |

United Kingdom | 66 | 2.62 | 208 | -44 | 645 |

Italy | 60.6 | 1.93 | 187 | -19 | 85 |

Canada | 36.7 | 1.65 | 149 | -7 | -1 |

United States | 325.7 | 19.39 | 147 | -21 | 27 |

Germany | 82.7 | 3.68 | 127 | -25 | 530 |

Japan | 126.8 | 4.87 | 127 | 4 | 17 |

South Africa | 56.7 | .35 | 116 | -2 | 773 |

Brazil | 209.3 | 2.06 | 95 | 54 | -29 |

China | 1386.4 | 12.24 | 91 | 278 | 14 |

Russia (post Soviet) | 144.5 | 1.58 | 85 | -28 | -6 |

India | 1339.2 | 2.6 | 84 | 156 | -53 |

Contributions of renewables are to energy production.

Growth in Participation of International Environmental Agreements↑

| Years from First Signature | Cities | Convention on Biological Diversity | Kyoto Protocol | Montreal Protocol | Paris Agreement | World Heritage Convention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | 6 | 30 | 5 | 30 | 121 | 1 |

2 | 21 | 90 | 21 | 52 | 172 | 10 |

3 | 31 | 127 | 31 | 65 | 184 | 20 |

4 | 40 | 162 | 45 | 73 | – | 26 |

5 | 48 | 169 | 100 | 96 | – | 34 |

6 | 56 | 174 | 119 | 130 | – | 42 |

7 | 62 | 176 | 132 | 145 | – | 48 |

8 | 72 | 178 | 156 | 150 | – | 55 |

9 | 76 | 181 | 168 | 160 | – | 60 |

10 | 81 | 186 | 176 | 162 | – | 69 |

11 | 84 | 187 | 183 | 167 | – | 77 |

12 | 88 | 188 | 189 | 171 | – | 82 |

13 | 92 | 189 | 191 | 174 | – | 87 |

14 | 93 | 190 | 191 | 183 | – | 90 |

15 | 95 | 191 | 191 | 184 | – | 98 |

16 | 103 | 193 | 192 | 186 | – | 105 |

17 | 108 | 193 | 192 | 188 | – | 108 |

18 | 111 | 193 | 192 | 189 | – | 113 |

19 | 117 | 193 | 192 | 191 | – | 121 |

20 | 120 | 193 | 192 | 191 | – | 130 |

21 | 128 | 194 | 192 | 193 | – | 136 |

22 | 130 | 196 | – | 196 | – | 139 |

23 | 134 | 196 | – | 196 | – | 145 |

24 | 143 | 196 | – | 196 | – | 146 |

25 | 145 | 196 | – | 197 | – | 151 |

26 | 147 | – | – | 197 | – | 155 |

27 | 152 | – | – | 197 | – | 157 |

28 | 156 | – | – | 197 | – | 161 |

29 | 159 | – | – | 197 | – | 167 |

30 | 163 | – | – | 197 | – | 175 |

31 | 166 | – | – | 197 | – | 177 |

32 | 168 | – | – | – | – | 178 |

33 | 169 | – | – | – | – | 181 |

34 | 172 | – | – | – | – | 184 |

35 | 174 | – | – | – | – | 185 |

36 | 175 | – | – | – | – | 185 |

37 | 175 | – | – | – | – | 186 |

38 | 175 | – | – | – | – | 187 |

39 | 177 | – | – | – | – | 189 |

40 | 179 | – | – | – | – | 190 |

41 | 180 | – | – | – | – | 190 |

42 | 181 | – | – | – | – | 191 |

43 | 183 | – | – | – | – | 191 |

44 | 183 | – | – | – | – | 193 |

45 | 183 | – | – | – | – | 193 |

46 | – | – | – | – | – | 193 |

Citation for this content: American University’s International Relations Online Degree